This week I will be writing about an issue near and dear to my heart: The stigma of self-diagnosis.

More specifically, many within the autism community see those who unofficially diagnose themselves with ASDs as anything from deluded, to attention seeking, to outright mockeries of “real” autistics. Simply put, this stereotype is unfair, privileged, and exclusionary. While overly enthusiastic and loose self- (and official!) diagnosis has become a legitimate problem in modern mental health, this does not excuse the painful polarization of the “official” and “wannabe” diagnostic camps.

Once upon a time, I too was a self-diagnosed wannabe aspie.

Eventually, after a long quest of many trials and adventures, I received a late-in-life diagnosis from a Real Doctor™! Up until that point I had been a nervous wreck, worried that without an official diagnosis no one would “believe me.”

It seemed that everywhere I looked the fact that I was only self-diagnosed was jumping out at me, rubbing salt into my self-conscious wounds: My profile on Wrong Planet wanted me to choose between the labels “Diagnosed” or “Undiagnosed”; I encountered people both on- and offline ranting about “self-DXers” who are just looking for attention; I saw complaints from neurotypicals on mainstream forums openly spewing disgust for Special Snowflakes throwing around the term “aspie” to feel unique. When I called my neurotypical ex-boyfriend—with whom I’d spent so long struggling against my flaws and challenges, floundering in our mutual confusion over my seemingly nonsensical deficits—to tell him that I finally realized what was “wrong” with me, that nothing was wrong at all and I’m just autistic, he reassuringly told me, “Oh, no, don’t say that! You’re a perfectly normal girl. You’re way too normal to have Asperger’s!”

I was miserable. I felt—knew—no one would take me seriously. I floated in a no-man’s land. No-aspie’s land: Neither normal nor autistic.

I “look too normal.” I make facial expressions and vary my vocal intonation in a way so blatantly off that neurotypicals read me as creepy, quirky, aloof, disingenuous, or annoying. And yet, I’m so expressive that autistics whisper to each other—figuratively, over the internet—that I’m “not a real aspie.” Even today, my public image hangs in constant paradoxical limbo. I apparently look like I should be normal, but there’s something so obviously odd about me that I inspire posts like this one from the Wrong Planet forums, in reference to my presence on Autism Talk TV:

…it appears that over time she has shaped her image, and adjusted her behaviors to appear more unkempt and awkward than she naturally is.

And even with my unkempt (haha) and awkward mannerisms, I’m always told that I pass as neurotypical very well, that no one would guess I were autistic if I weren’t so open about it. I understand what these statements really mean: You don’t fit the stereotypical image of autistic, with your expressive face and your excited voice.

It’s funny that the context of the autism community so alters expectations that many feel I seem “normal” in comparison. I’d love to find a way to shove those comments in the faces of all the neurotypicals over the years who have hated and resented me for my abnormalities.

Thus, the frustration of limbo.

All tolled, this is why I sought a diagnosis. This is why, for me, a diagnosis was worth the time, insurance battles, and repeated humiliations (I still resent that therapist who told me I “can’t have autism” because I “have friends, and a boyfriend”).

Sure, I wanted to see what extra services my school could provide that might have helped me. But mostly, it was that I wasn’t comfortable speaking publicly about autism on platforms such as Wrong Planet’s Autism Talk TV without an official diagnosis. Not because I wasn’t absolutely certain of my autism, but because I knew there would be painful backlash if I went public without a “real” diagnosis.

Without that doctor signing that paper saying that he agreed with me, I would have been mocked and dismissed.

The politics of self-diagnosis most heavily influence those who are the best at passing for neurotypical. Even those who doubt the more obviously autistic self-diagnosers still admit that they’re probably autistic, or, if not autistic, something. But those of us who don’t look have the stereotypically blank faces, who talk, who have friends, we are seen as hypochondriacs, attention-seekers, and—shudder—“normal” people just wishing for a taste of the extraordinary.

Many autistics who do fit the stereotypes seem to jump to the conclusion that any autistic who is talkative, extraverted, artistic, friendly, or otherwise not like themselves must be “milder cases” of autism. But they forget that autism has little to do with introversion or extraversion,* artistic or mechanical talent, taste in clothing and music, or any other unrelated piece of personal identity.

As a hyperlexic, chatty-but-introverted, artistic, logical, and energetic autistic with a special interest for human social interaction and nonverbal communication, I’m often read as having one foot in both worlds. Though it would be more accurate to say I have three thousand feet and they’re all tangled up and sprawling across every world with no discernible rhyme or reason.

I’ve also encountered many self-diagnosed autistics who simply come from poor backgrounds. Growing up, they had those same problems we all dealt with, but they were never taken to a doctor for assessment because their parents didn’t have the time, the money, or the insurance coverage to handle a multi-thousand-dollar battery of tests to confirm what they already knew about their child: Ayup, your kid has problems alright.

I’ve talked with adults who were undoubtedly autistic—describing their travails in rapid-fire unceasing monotone while stimming like nervous mice—who felt ashamed or embarrassed to openly join the larger autistic community because they didn’t have the medical insurance to cover a diagnosis. They too felt that no one would believe them, and felt the pain of that diagnostic limbo.

Some were less obviously autistic to the untrained eye: Women who shone with tangible relief when I told them I agreed with their self-assessments, smiling and laughing like TV personalities while tapping their feet to the beat of a machine gun and compulsively twirling their hair; men who shook hands all day at busy networking jobs and then collapsed at the end of each day, exhausted from the effort of maintaining the façade.

These people seem to worry the most. They felt that they’d “waited too long,” they “faked it too well,” and they didn’t want to have to go through the effort of a diagnostic assessment just to prove themselves to the world.

This phenomenon of the adult autistic is another important fact often ignored by autistics that rail on self-diagnosis; the majority of middle-aged autistics are self-diagnosed!

There were just as many aspies in previous generations as there are today, so it follows that those who never got those late-in-life diagnoses, after Asperger’s went vogue, are still out there. While many autistic adults who learn of ASD and recognize it in themselves decide to undergo the lengthy trials that involve an official diagnosis, many late-in-life DXers simply don’t see the point. While they understand that they fit under the umbrella of ASD, they don’t pursue diagnosis. They are “self-diagnosed.”

It bears mentioning here that while I referred to myself earlier as receiving a late-in-life diagnosis, my diagnosis came far sooner than many, as late diagnoses go: I was only nineteen. Some adults spend decades wondering, or struggling with their identities, always feeling different (or labeled as different by their peers) and never knowing why, until finally in middle age they come across a particularly poignant description of ASD, and everything just clicks. They look up from their computer screens and gasp, thinking, “Oh my gosh, I finally understand.”

But what if these hypothetical middle-aged autistics are functional adults, fully integrated into society, with friends, spouses, children, and successful lives, who have learned to compensate and work around their symptoms and disabilities? Many are. What if these adults don’t have the money, time, or insurance-coverage for an official diagnosis? Many don’t. They aren’t in school, so they don’t need additional disability services. They aren’t dealing with any financial or legal situations that may require documentation of disability. They don’t have a pressing need for that rubber stamp that justifies the literal and figurative costs to a “real” diagnosis. Thus, they become “self-diagnosed.”

Diagnosis, and the problems that arise from the self-diagnosis stigma, can be especially problematic for adult women.

The reason I am seen as having “a milder case” of autism, when compared to people like Alex Plank, the founder of Wrong Planet, or my ex-boyfriend, Jack Robison, is the same reason that other autistic women are often overlooked entirely, or judged harshly when they reveal their self-diagnoses. I smile, I laugh, I make facial expressions, I gesticulate when I talk, I can even break out of my monotone voice if I focus.

Some of these things I do naturally. I’ve always been giggly, even as a baby. But when 17-year-old me first started dating that neurotypical ex I mentioned earlier, I was a hunched, monotone aspie stereotype; my only gesticulations were fidgets and stims, my standard affect flat as a board. Sure I laughed, but that wasn’t enough. I could break out of my flat affect to copy those around me, and I went through the unfortunate phase common to many autistic girls of copying facial expressions and vocal intonations from Japanese anime. But my normal baseline was such that any aspie on Wrong Planet would have ranked me in line with themselves, as they rightly should. That high school ex taught me to be self-aware and to seek improvement. I honestly hadn’t noticed I was different until he came along. I stopped holding contorted faces while zoning out (for the most part), I stopped curling my hands in front of me like a T-Rex, I worked harder to move my face and my voice in natural ways, I learned to reciprocate social niceties. In short, I learned how to pass.

I will write more on this in the future, as this topic deserves far more attention, but for now I will try to summarize: The reason that women on the spectrum present so differently, often appearing more “mild” in their autism, is because women are trained from babyhood to fit an entirely different role than men.

Girls are taught a type of bodily and social self-awareness rarely imposed on boys, and girls form social bonds in ways that encourage the collective training of these skills. The chasm widens with puberty, and grown women are held to a nearly invisible yet powerful standard that enforces further divide between the presented symptoms of autistic women and men. Grown autistic women will often hop from diagnosis to diagnosis, displaying symptoms for depression, anxiety, and other emerging pieces of the puzzle caused by the larger issue of their undiagnosed autism. By the time an adult woman suspects she could be autistic, she may have long since learned to read and utilize nonverbal language, to conduct herself in a manner that—while not as fluid and natural as that of a neurotypical woman—passes for normal. She has learned cognitive empathy, conscientiousness, self-awareness, and other skills she used to struggle with. Due to her upbringing, her special interests may be natural diapering techniques, hair care, and medical dramas instead of guns, trains, and antique cars. While she may have fit the DSM criteria as a little girl, these days she is turned away by specialists like the one who told me I couldn’t have autism because I have friends.

While every kid that doesn’t meet the cookie-cutter mold of the horrific American school system is being slapped with pathological labels these days, this doesn’t mean that self-diagnosis of autism is meaningless.

Autism is incredibly common.

Official diagnostics report an occurrence rate of 1 in 68, and we already know that diagnostic numbers are not always an accurate representation of reality. Instead of assuming that someone isn’t a “real” autistic unless they’re exactly like you, or your child, or that one guy on TV, remember that every autistic is unique. Trust that most who identify as self-diagnosed have put long thought and research into their decisions, and give them the benefit of the doubt. Remember that when someone self-diagnosed receives a “real” diagnosis, all that implies is a doctor agreeing with what they already knew.

I know that we autistics are prone to black-and-white thinking, but try to keep an open mind. People self-diagnose for a reason. If someone feels they meet the diagnostic criteria, and identify with the autism phenotype, I tend to trust them. I was there once; I remember how it feels.

_____________________________________________________________

* Footnote: I’m sure my comment about introversion and extraversion will raise some eyebrows, so I figured I should elaborate. While many people assume that all autistics must be introverted, because we are by design less socially-apt, this is not the case. Not only that, but the definitions of these words are often mistaken. An introvert is not someone who disdains company, or who doesn’t like socializing. An introvert is someone who requires energy to socialize, while an extravert is someone who gains energy from social interaction. I am an introvert. I love going to parties, social events, and seeing my friends, but after a full day of hanging out and talking with other people I’m going to be tired and spent. I’ll have the time of my life at a conference, and at the end of the day collapse onto my hotel room bed, exhausted and needing to recharge. My friend Alex Plank is an extrovert. After a full day of filming and interviewing for Autism Talk TV at a conference, while I’m a drained mess who’d like nothing more than to stay in bed for the rest of the week, Alex will pace the room like a caged animal talking about how he wants to go back out and keep socializing. An extravert gets lonely very quickly, and will come down with a lethargic case of cabin fever when left alone too long. An introvert will get this lethargic drained feeling from socializing too much. Extraverts recharge their batteries by interacting with others, introverts recharge their batteries by relaxing and resetting.

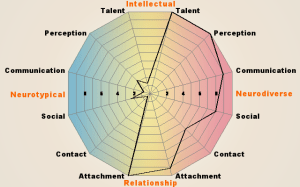

EDIT: Considering the topic of this post, I wanted to share my all-time favorite free online autism assessment: The Aspie Quiz. Yes, the name is a little casual and silly, but it’s a wonderfully detailed questionnaire undergoing constant recalibration based on the data compiled over time. The quiz even includes unrelated control questions, and multiple versions of the same questions, to control for intentional manipulation of one’s results. Also, the results are displayed using a spider diagram, one of the best methods I’ve seen to deal with the non-linear nature of the autism “spectrum.” For example, my results look like this:

Of course, no online quiz is perfect, and even this quiz can’t include every variation of autistic. But for those of you out there who for whatever reason do not have access to an official diagnosis, online resources like these can be very helpful!

Hi Kirsten,

You didn’t quote me. 😦

LikeLike

Haha– Are you that person from WrongPlanet then? I didn’t feel comfortable using the username in the quote without the knowledge of the person posting! I’ll take this as permission 😛

LikeLike

ImAnAspie – the dubbing ceremony comment. I’d be honored if you quote me 🙂

LikeLike

ahhhh! I see. I’ll try to work that in to my next post!

LikeLike

Love your post. I, too, am self-diagnosed. I had been wondering for years, well, decades, about what was off with me. My older son has Asperger’s and over time I began looking over different sites about Asperger’s and saw a list by a female Aspie. I have almost all 100 of those traits. Finally, I know that I am not crazy, but have this ‘uniqueness’ about me. I have peace now. I have an understanding of who I truly am.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment! It seems that your story is a fairly common scenario, actually. I’ve heard from so many parents who didn’t realize that their differences fit under the autism umbrella until their kids were diagnosed. Researching the condition then leads to that “Ah ha! These traits fit ME too” moment for a lot of people, I think. Of course, there are also those parents Stephen Shore refers to as “aphids” (Autistic Parent Heavily In Denial).

LikeLike

I really appreciate this article addressing self-diagnosis as a legitimate way to identify one’s own mental patterns! And your discussion of how economic class can play a huge role in the availability of a “real” diagnosis!

LikeLike

Thank you for this post! It means a lot to me since I can relate to SO MUCH of what you write. As a young woman who only discovered her autism after reaching adulthood, I too felt that I had to prove my self-diagnosis by getting a “real” one before I could be taken seriously. I was afraid to tell people or to participate online unless I had it, and this really stressed me out. (I actually waited months before making my Wrong Planet account so I could put “diagnosed” on my profile.) But, just like you said, for an adult who has done their research, all the doctor is really going to do is agree with what they already know. Thank you for such a comprehensive discussion of the reasons why people might not pursue an official diagnosis. For many, it just isn’t an option. I think that if someone is very serious about being autistic, there is very little reason to doubt them.

The reception I got regarding my autism was basically split between two camps: those who had known me through the years when I was a stiff, awkward, oddly dressed, monotone, expressionless teenager with an obviously displayed special interest, and those who had met me during the years after I’d “learned to pass.” The people who had known me longer were inclined to agree that autism fit, but to the majority it was a big surprise. It doesn’t help that most people don’t know much about autism at all. (How are there still so many stupid ideas circulating like you can’t be autistic if you have a relationship, friends, a job, or even emotions?!) The prevailing attitude really is against women on the spectrum because it seems that if you can physically present yourself as “normal” (let alone if you’re pretty) and know how to get by, people are going to doubt you’re actually autistic. Since girls are socialized to care about how they look and how they are socially perceived, it only figures that we tend to learn that stuff more.

I’ve never doubted that you’re a “real aspie.” You’re about as real as they get! It doesn’t matter how you decide to present yourself or how “well” you can act on any given day. And of course it isn’t all acting: Aren’t we all continually learning and growing? Personally, I’m glad we aspie women have you as an advocate because I’m more than pleased to have you represent me, and others like us, to the world.

LikeLike

I nominated you for this liebster award thing that’s going around! ~ derp derp! here’s a link to my post: http://lizzieleee.wordpress.com/2014/03/12/liebster/

LikeLike

[…] Selbstdiagnose, Selbstakzeptanz […]

LikeLike

[…] prefer Amy Sequenzia’s approach, which is also the position that ASAN takes, and that many members of our community (and researchers) share as well. *This* is how we learn how to share and grow […]

LikeLike

Hi Kirsten!

I love your content, especially on relationships which has helped me personally. This is an old post, I know but I wanted to know your thoughts on self-diagnosis. As a once misdiagnosed, now formally diagnosed adult female on the spectrum, I fully understand the lack of availability of experts for adult female diagnosis. I recognize that the majority of self-diagnosed individuals are correct in their suspicions and are often well-researched before committing to the label. I would even recommend against a formal diagnosis if a person is satisfied with their own validation and would not take advantage of any additional supports.

I am concerned however about the growing number of self-diagnosed individuals who use only the AQ50 and Samantha Craft’s checklist for women as their sole methods of validation. These checks have high rates of false positives (see also: “You will continue to interpret vague statements as uniquely meaningful”). I have noted many self-diagnosed individuals dominating conversations about changing the diagnostic criteria to be more inclusive of comorbidities such as anxiety and EF deficits so that they would be captured. While commonly experienced by some individuals with autism, their experiences change the very dialogue of what autism is.

The inclusion of voices who do not have ASD into the community is a risk that we accept in order to ensure that the larger majority of correctly self-diagnosed individuals have a place to find support and peer resources.

I would argue that this risk could be mitigated by community support of specific evidence-based tools which are not gender-biased such as the RAADS-R, relatives questionnaire, EQ and SQ. The AQ is the most well known and as a community, I think we do a terrible job of promoting it without highlighting its high rate of false positives.

If neurologists were in short supply, it would make me very sympathetic to those waiting to see one, however it wouldn’t make it okay to self-diagnose. It would be useful to collect data and learn about potential diagnoses, but it’s an entirely different thing to tell people you have brain cancer and start speaking at brain-cancer survivor conferences.

Love to hear your thoughts 5 years later 🙂

LikeLike

Kirsten, you completely nailed this subject.

It is as if some people believe that it is the diagnosis that makes someone fully autistic – an horse before the cart scenario.

I think you are definitely autistic and were so before you were diagnosed as well as afterwards (obviously).

You have a talent for expressing things clearly and this post will help many people who are going through the self diagnosis wilderness. It can be dreadful realising nearly all the criteria fit but then feeling guilty for “wanting to be special” or “seeking attention” or “making it all up” by seeking only evidence that confirms your bias. I’d suggest most aspies would be capable of judging their past objectively.

Many older people will be keeping their self diagnosis a secret from colleagues and even family and will not be keen to draw attention to it.

It is helpful to read what you went through. I think you have a desire to know yourself and help others and are no more an attention seeker than anyone else.

LikeLike